|

I want to begin with the earliest representations of men and women in the early modern period in Western art. By "early modern" I mean the Renaissance in Europe (the 15th and 16th centuries) and I choose Western art because it is the dominant historical influence on European and eventually on American culture. The earliest representations of actual men and women occur in portraits, a form which developed in the 15th century. Before the Renaissance the men and women represented in art were primarily religious and Biblical and mythical figures, but in the 15th century the portrait developed--that is, the representation of an actual, living human being. Those depicted in these portraits were the wealthy and privileged, because they were the only ones who could afford to commission paintings of themselves or their loved ones. In fact, for several centuries (until about the nineteenth century) most of the men and women represented in portraits (unless they were related to an artist) were of the elite, privileged class. Most of these portraits share one common trait: they represent idealized versions of the wealthy. The symbols of their status often have a prominent role in the portrait, whether heraldic devices to indicate lineage, ornaments and jewelry to signify wealth, or symbolic attributes in the background to suggest particular virtues or accomplishments. The examples below, ranging from the 15th to the 17th century, are typical. |

|

|

Left: Titian, Portrait of Philip II, 1551

center: Titian, Portrait of a Man, 1508 |

Center: Memling, Portrait of Maria Baroncelli, 1470

right: Rembrandt, Portrait of Maria Trip, 1639 |

|

|

In this general sense these early portraits of men and women are alike. The differences, however, are telling. Not only are the women usually more elaborately dressed in expensive fabrics, sometimes embellished with gold, they also wear expensive and beautiful jewelry. In evaluating what from a modern viewpoint appears to be vanity, we should be careful. Women in Renaissance society may have been privileged but they were usually unempowered. Their portraits were designed for the male viewers; the women are passive, powerless objects subject to the controlling gaze of males. These males, their husbands or fathers, wanted affirmation of their own status. Women's clothing and jewelry provided an obvious and public demonstration of a family's wealth (Tinagli 51). Female bodies are thus used to display the male accumulation of power and wealth.

It is also the case that the women portrayed may be wearing jewels that were part of the dowry or special wedding gifts; thus, it is important to their families that these women display their finery. |

|

Fra Filippo Lippi, Woman with a Man at the Window, c. 1438/1444 |

| In this puzzling double portrait (the male peaks in the window) by Fra Filippo Lippi the lavishly dressed bride wears both a shoulder brooch and head brooch, traditional groom's gifts in Florence Italy. As Dale Kent explains, "Marking her with dresses and jewels, often bearing his crest, by bestowing on her a ritual wedding wardrobe the husband introduced his wife into his kin group and signaled the rights he had acquired over her. Most of the items remained the property of the husband, who might later bequeath them to his wife or repossess them; if he needed capital, they could be sold" (30).

The woman in this painting wears pearls and more pearls--a shoulder brooch with a diamond and pearls, a pearl head brooch, a headdress decorated with hundreds of seed pearls, a cap edged with pearls, and the motto "LEALT�" (or loyalty) spelled out in pearls on her sleeve. They have an important role in constructing the identity of this young woman. Not only were pearls the most expensive gem in the 15th century, they were also a common symbol for purity or chastity. Since pearls signified virginity, they were a common gift to brides. Dogs serve the same symbolic function in portraits of women. Here in this 16th century marriage portrait of a noblewoman (red was the color of the marriage gown), the small dog (as in Fido=fides=faithful) serves as a symbol for marital fidelity . |

Lavinia Fontana, Portrait of a Noblewoman, c. 1580 |

|

| Virtuous sexual behavior was in fact the most important quality in a maiden or wife. As St. Bernardino preached in Florence, "a woman's betrayal of her husband is more serious than a husband's betrayal of his wife, because 'she has no other virtue to lose'" (Tinagli 24). Repeat: she has no other virtue to lose. And presumably men have many virtues.

Perhaps this explains the popularity for several centuries in western art of one story inherited from Roman history and legend--the story of Lucretia. A quick search turned up more than 50 paintings based on the legend. According to the story, Lucretia, a married woman, was raped by the son of a Roman king. Because she had been dishonored, by no act of her own volition, she did the honorable thing and committed suicide. She is sometimes depicted being raped but more often in the act of doing the honorable deed. The rape is depicted by Titian, a 16th century male painter, the suicide by Artemisia Gentileschi, a 17th century female painter. |

|

|

Left: Titian, Tarquin and Lucretia, before 1571

center: Artemesia Gentileschi, Lucretia, c. 1611 |

| This emphasis on female virtue explains much in the depiction of women, as contrasted with that of men. It sometimes explains the pose. A stiff, upright posture indicated virtue; downcast eyes or an averted gaze also indicated virtue. (See below.) At some time periods head coverings were important. According to Church law "a woman ought to cover her head since she is not in the image of God. She ought to wear this sign in order that she may be shown as subordinate and because error was started through a woman" (Kent 36). |

Center: Rogier van der Weyden, Portrait of a Lady, c. 1460

right: Judith Leyster, Self Portrait, c. 1635

|

|

|

|

Even the position of the arms--which needed to be close to the body--was significant. This Self-Portrait of the 17th century artist Judith Leyster was daring, for she painted herself in a very relaxed, casual pose with her painting arm balanced on the chair. As late as the 18th century, the woman's pose was still crucial: she "could not show [her] teeth, could not show [her] hair unbound, could not gesticulate, and certainly could not cross her legs" (Borzello 32). |

|

Thomas Gainsborough, Mrs. Philip Thicknesse, 1759-60This portrait by the eighteenth century British painter Thomas Gainsborough was thought unseemly because of the crossed legs of the sitter. Of the woman in this painting, one critic said "handsome and bold; but I should be very sorry to have anyone I loved set forth in such a manner" (quoted in Borzello 32). |

|

No such standards governed the portrayal of male sitters. Their virtue is never at issue. Or, if it is, their virtue can be regained. For example, one of Rembrandt's most famous paintings is this double portrait of himself and his wife Saskia in a tavern. This painting is generally interpreted as Rembrandt's self-criticism since he relies on the traditional depiction of the prodigal son. |

Rembrandt, Rembrandt and Saskia in the Scene of the Prodigal Son in the Tavern, c. 1635 |

|

| Here the flamboyantly dressed young rake displays his flagon of ale while his wife plays the role of a bar room harlot. While the Biblical parable may symbolically apply to both men and women, we know that for centuries once a woman was ruined, it was a road with no return. No painting could depict a prodigal daughter. There was a double standard then--as there is today.

There are a few examples in the 16th and 17th centuries of women artists, that is, somewhat independent women who made a good living painting. But independent women were suspect, perhaps of easy virtue since not under the thumb of father or husband. Note how they depict themselves. Here is one of Sofonisba Anguissola's self portraits. |

|

|

Left: Sofonisba Anguissola, Self Portrait, 1554

center: Sofonisba Anguissola, Self Portrait, 1561 |

| Like most of the portraits we have looked at, this likeness is pretty straightforwardly realistic without much in the way of psychological revelation. But she is much more simply dressed than the aristocrats we have seen and she looks at the viewer solemnly with large serious eyes. The inscription is important; it reads "Sofonisba Angussola virgo seipsam fecit 1554." She introduces herself as a virgin. Other self portraits by Anguissola depict her holding a book or playing a musical instrument, which is a way of saying she is not an artisan/craftsperson but of noble birth, cultured and elite. (She did in fact receive a humanistic education.) But at least as important in the self portrait with the spinet is the presence of the woman in the background, generally interpreted as a chaperone. This is yet another way of assuring the viewer that she is a proper young maiden. Later women artists make the same claims. Here Lavinia Fontana follows Anguissola's lead in asserting her modesty and later the pastellist Rosalba Carriera depicts herself with a portrait of her sister, a way of claiming her protection. |

Center: Lavinia Fontana, Self Portrait, 1577

right: Rosalba Carriera, Self Portrait Holding Portrait of her Sister, 1715

|

|

|

| I know of no paintings of men or boys with chaperones unless we want to consider this charming of portrait of the young Stampa (with a dog as chaperone!?) an example. This 9-year old wears mourning because his father has recently died; thus he is the new marchese. |

|

Sofonisba Anguissola, Portrait of Massimiliano Stampa, 1557(Actually the dog may be symbolic since a dog appears on the Stampa coat of arms and in any case, the dog is scarcely a vigilant chaperone.) |

Men are often depicted with symbols of their accomplishments. In this double portrait by Holbein, the ambassadors are accompanied by symbols of their learning and interests: mathematical and astronomical objects, compasses, sundial, globes, a lute, and a hymnbook. Here's a geographer. |

|

|

Left: Holbein, The French Ambassadors, 1533

center: Vermeer, The Geographer, 1668

|

Open books are common attributes in male portraits as a way of indicating their intellectual interests.Center: Bronzino, Ugolino Martelli, c. 1535

right: Hans Holbein, Erasmus, 1523 |

|

|

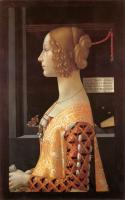

With the exception of women artists who sometimes depict themselves before an easel, portraits of women generally have few added accoutrements. Here, for example, we see only a rosary (the coral beads) and the prayer book. Again, it is her virtue, in this case her piety, that is all-importantDomenico Ghirlandaio, Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni, c. 1488 |

|

The woman in this painting was 20, the age at which she died in her second childbirth. Most of the portraits we have seen of women depict them as young women, rarely even middle-aged. Sad to say, but until the present century, after child-bearing years, women weren't worth much; at least they weren't worth commemorating in expensive portraits. There are many portraits of older men, men distinguished by their accomplishments. |

|

|

Raphael, Pope Julius II, c. 1512

Antonio Rossellino, Giovanni Chellini, 1456 |

|

Benedetto da Maiano, Pietro Mellini, 1474-6 |

Antonio Rossellino, Matteo Palmieri, 1468Palmieri, the Renaissance humanist depicted here, provides the rationale for such portraits of old men; he says "What learning the old possess, what rich precepts they command. How often do his family, his friends, his fellow citizens hasten to consult an eminent old man. No longer able to exercise his body, he exerts his mind, and his deeds and sayings are recorded for posterity" [quoted in Pope-Hennessey 77]. |

|

| But older women, unless they are related to the artist (like the famous painting of Rembrandt's mother) have rarely been depicted. The 16th century woman painter Anguissola, well-known in her own time, did, however, feel she was worth painting in her 70s and later her 80s. |

|

|

Anguissola, Self Portrait, 1610 and 1620 |

| As a famous painter who had lived for decades in the Spanish royal palace, she had a strong sense of her own worth. Later, the woman painter Rosalba Carriera painted herself as an elderly woman, personified as winter. But the point remains: the visual evidence suggests that men get older and wiser; thus, worth commemorating in paintings. Women just get old.

|

In the history of western art I know of few portraits of elderly women done by male painters (unless they were related to the artist) so this one by the 19th century French painter Ingres is remarkable; at least it's remarkable that the countess's son commissioned this work.Ingres, Portrait of the Countess of Tournon, 1812 |

|

|

I suppose she isn't really elderly by today's standards. She's a mere 60. Although Ingres is known for his realism, it's clear that he idealized this older woman in an age when plastic surgery wasn't available. Although there is still the faint suggestion of a mustache, if she had wrinkles on her forehead, they are covered by the curls of her hair (possibly a wig); her double chin is minimized by the lace ruff, and scholars have even suggested that Ingres used the arms of his young wife as the model for the aging countess's arms. Men can have wrinkles, fat arms, sagging chins; the artist must work magic on an older woman.

|