This grandiose church was begun as the largest in Russia and fourth in size in Europe after St. Peter's in Rome, St. Paul's in London, and the Duomo in Florence. It is the second tallest (101.5 m) in St. Petersburg after Peter and Paul Cathedral. It was built on a site where earlier churches were in disrepair. The new cathedral was dedicated to St. Isaac, whose saint's day in the church calendar, May 30, was also the date of Peter the Great's birthday. This date in the czar's life was probably more important in the naming of the cathedral than any event in the life of Isaac of Dalmatia. Left: from the northwest; Center: from the southeast; right: from west | ||

|

|

|

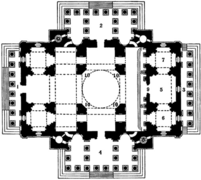

| The church has a Greek-cross plan oriented strictly to compass directions with porches at the ends of each of the compass axes. William Craft Brumfield describes the plan as "inscribed cross," "but with a longitudinal extension in the manner of a basilica," (400) adding that the fusion of different Christian architectural traditions is a hallmark of this cathedral. For example, this Russian Orthodox church even has a large stained-glass window in the main altar. The east side is the altar end; thus there is no entrance on the east side. The 100 by 100 meter rectangle is supported by the eight and sixteen columned porticos. This essentially horizontal structure is crowned by a 25 meter (more than 80 feet) dome made of iron and covered with gold plated copper, surrounded by a colonnade, the balustrade of which has 24 bronze statues of angels (copies of originals) by Pyotr Klodt after the model by Joseph German (Akindinova 225). Each corner of the lower structure has a belltower, originally planned as a smaller cupola. A gold gilded lantern, in restoration in this picture, surmounts the dome which supports a 6 meter high gilded cross. |  | |

| The sculptural decoration of the cathedral is important, for stylistic as well as theological and political reasons. Tatiana Akindinova says that "all details related to the cathedral's decoration were subjects of discussion and approval by the Synod and the ad hoc government committee" and the subject matter was designed to explain both the theological point of Christ's redemptive mission but also to assert the union of church and state. (221) The French architect Montferrand "gathered around him a group of brilliant sculptors of the time--Ivan Vitali, Philippe Henri Lemaire, Pyotr Klodt, Nikolai Pimenov, Joseph German, Alexander Loganovsky and some others--who executed sculptures from his drawings. The leading role in this team belonged to the Russian sculptor of Italian origin Ivan Vitali . . . who executed over three hundred statues and reliefs as well as the design of two pediments, plastic imagery of the inner and outer doors, the drum and the dome" (221). The roof area has at least 210 bas-reliefs, busts and statues. The attic corners have pairs of angels (by Vitali) holding gas torches that were lit at Easter. (See central photo below.) The peak of each of the pediments bears a statue of one of the four Evangelists while the corners have figures of the Apostles. | ||

|

|

|

| A bronze statue of the Evangelist St Matthew, with his symbol, the angel, occupies the top of the pediment while sculptures of Andrew and Philip occupy the corners. | ||

South Pediment with Adoration of the Magi by Ivan VitaliThe realistic figures of the Magi are almost in the round with the heads of the Ethiopian King and his page from life. |

|

|

|

|

Coffered ceiling of the porch |

South porchThe south portico has an enormous double shuttered door made from electroplated or cast bronze over solid oak. The relief panels are in registers and recall the doors of the Baptistry in Florence by the masterful sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti, a noted influence on a number of Russian artists and architects. (See the Ghiberti doors here.) |

| |

|

|

The south doorThe pediment above depicts the Visitation of the Magi while the door below continues the theme of Jesus' younger years. In the topmost relief we see the presentation in the temple with Simeon holding the infant. |

Reliefs depicting left, the fight into Egypt (with the donkey peering in at the right) and right, Christ with the PhariseesJesus emphasizes his teaching with the forceful gesture. |

< |

|

|

|

The largest reliefs with left, St. Alexander Nevsky and right, the Archangel MichaelBoth Nevsky, the iconic military hero, and Michael, the special protector of the Russian throne, play special roles in the Orthodox tradition of Russia. Even though the sculptural reliefs have special meaning in the Russian tradition, the church as a whole is more in line with the European tradition. The architecture is classical and sculptural decoration goes back to the medieval European church. In Russia we think of icons, not sculpture as the supreme religious expression. |

The western doorThis door opens into the main axis of the cathedral and reveals within the glorious attar and decoration. The topmost relief continues the narrative of Christ's life, here depicting the Sermon on the Mount with Christ seated above the rapt listeners (except for the two doubters on the left). Below are other events in His life, both healing miracles: the raising of Lazarus on the left and His healing of the bedridden man on the right. These reliefs underline Christ's saving of the soul, through teaching, and saving of the body. The large figural reliefs depict Peter and Paul, Peter depicted with the familiar key. These early Christian apostles are important in the Russian tradition as evidenced by the first church built in the new city of St Petersburg, the Peter and Paul Cathedral. These names were also given to members of the Russian throne. | ||

|

|

|

| I find the conclusion to Tatiana Akindinova's essay worth quoting: "Built in the atmosphere of patriotic feelings after the defeat of Napoleon, the cathedral was to demonstrate the might of Russia and to become a symbol of Russia's unity with the Christian culture of Europe" (234). | ||

Click here to return to index of art historical sites.

Click here to return to index of art historical sites.

Click here to return to index of artists and architects.

Click here to return to index of artists and architects.

Click here to return to chronological index.

Click here to return to chronological index.

Click here to see the home page of Bluffton University.

Click here to see the home page of Bluffton University.