Degas, Portraits in an Office--The Cotton Exchange, New Orleans, 1873

Vermeer, The Lacemaker, c. 1671-2; Vermeer, The Milkmaid, c.1659-60; Jean-François Millet, The Gleaners, 1857

Courbet, The Grain Sifters, 1855; Daumier, The Burden (a Laundress), c. 1860; Degas, Laundry-girls ironing, c. 1884

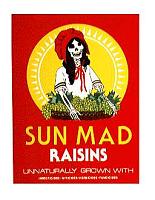

These are of course the women who worked since wealthy women had everything done for them. Sometimes the women who do this back-breaking or blinding work are depicted sympathetically, but no artist is quite as hard hitting as the contemporary Chicana artist, Ester Hernandez, who reminds us that such gendered (and racist) employment has large implications.

Ester Hernandez, Sun Mad, 1982

Occasionally the history of art makes us aware in dramatic ways of the situation of women who attempt to work outside their defined roles.

In contrast, the woman artist Emily Mary Osborn at about the same time in England painted Nameless and Friendless, a painting which tells a story sympathetic to a working woman's plight.

Emily Mary Osborn, Nameless and Friendless, 1857

The woman in black (a recent widow perhaps) depends on her artistic abilities to make her way in the world. At the art gallery she is not asked to sit, a clear sign that she is poor, while her work is inspected by the art dealer who holds her fate in his hands. At the same time she is inspected with prurient eyes by the men on the left.Left and center: Vermeer, The Procuress, 1656

right: Judith Leyster, The Proposition, 1631

In the 19th century, Manet shows this sexual employment as almost glamorous. Here is Nana, as Linda Nochlin says, "staring brazenly out at us, accepting her status as object with a wink of complicity, the pictorial embodiment of the male chauvinist dreams of Second Empire Paris" (29). 2 Contrast, for example, Manet's Portrait of Zola, the author of the novel about prostitution in which Nana occurs. He is dignified and cultured, an intellectual surrounded by books and works of art. According to the artist Manet, Zola's is the life of the mind, Nana's the life of the body.