Depictions of male and female nudes

Before going to some of the changes that occurred in the 18th century and later I want to consider one last image of men and women: the depiction of the nude figure. When you think of the nude figure, you may think primarily of the female nude, which has been and continues to be the obsession of male artists. However, in the history of art, understanding the male nude was a requirement of artists, the basis of art training. There are striking differences in these two images. Margaret Walters explains that "Over the centuries of Western civilization, the male nude has carried a much wider range of meanings, political, religious and moral, than the female. The male nude is typically public: he strides through city squares, guards public buildings, is worshipped in the church. He personifies communal pride or aspiration. The female nude, on the other hand, comes into her own only when art is geared to the tastes and erotic fantasies of private consumers" (8). The male nude typically represents power, virility, courage, sometimes is even defined as spiritual beauty--all qualities used to describe this 14 foot sculpture of the Biblical hero David, which for centuries stood in one of the main squares in Florence.

Michelangelo, David, 1501-4

This work was a symbol of Florentine liberty, a Florence which like David, had defeated a much stronger enemy. It is most unlikely that the Biblical hero strode out to defeat Goliath in his birthday suit, but Michelangelo depicts him nude because traditionally heroes were depicted that way--whether Greek gods, Hercules, or the Classical virtue, Fortitude.I'd like to add that prior to the installation of Michelangelo's David in its prime public location, another work had been in that spot: Donatello's Judith and Holofernes. This Biblical story is one of the few with a female protagonist. Judith, the Israelite heroine, sneaked into the Assyrian camp where she seduced Holofernes by getting him drunk and then beheaded him. In so doing she was a savior of her people. But this tribute to female heroism was removed. A few years later two additional works were erected nearby in the Loggia dei Lanzi, works which are hardly positive in their attitudes toward women: Cellini's Perseus and Medusa with a male hero holding up the head of the dreaded female Medusa and Giovanni Bologna's Rape of the Sabine Women.

Left: Donatello, Judith and Holofernes, 1455-60; center: Cellini, Perseus and Medusa, 1545-54; Giovanni Bologna, Rape of the Sabine Women, 1583

Canova, Napoleon, 1809-11

The idea of the heroic male nude continued well into the 19th century; here Napoleon, who certainly wore a fabulous uniform on the field of battle, is sculpted like a nude Greek god. Perish the thought that his nudity has any sexual resonance.

Giorgione, Venus, c.1510

When artists began to depict the nude female in the 16th century, she is depicted as passive (not active like the male nude); this suggests her availability to the male viewer. This depiction is fairly constant in the history of art.Velazquez, Venus at her Mirror, 1649-51 and Rembrandt, Dana�, 1636

Ingres, Odalisque, 1814; Goya, Nude Maja, 1800

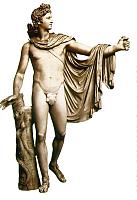

Dürer, The Fall of Man, 1504; Apollo Belvedere, Roman copy of a Greek original from the fifth century BC

The idealized male body is based on the Apollo Belvedere, a famous surviving Greek statue.By the 17th century, the female nude becomes more popular than the male nude and by the Nineteenth century, the term nude pretty much means the female figure. The contradictory attitudes about nakedness in the Victorian period and later are too complicated for explanation here.